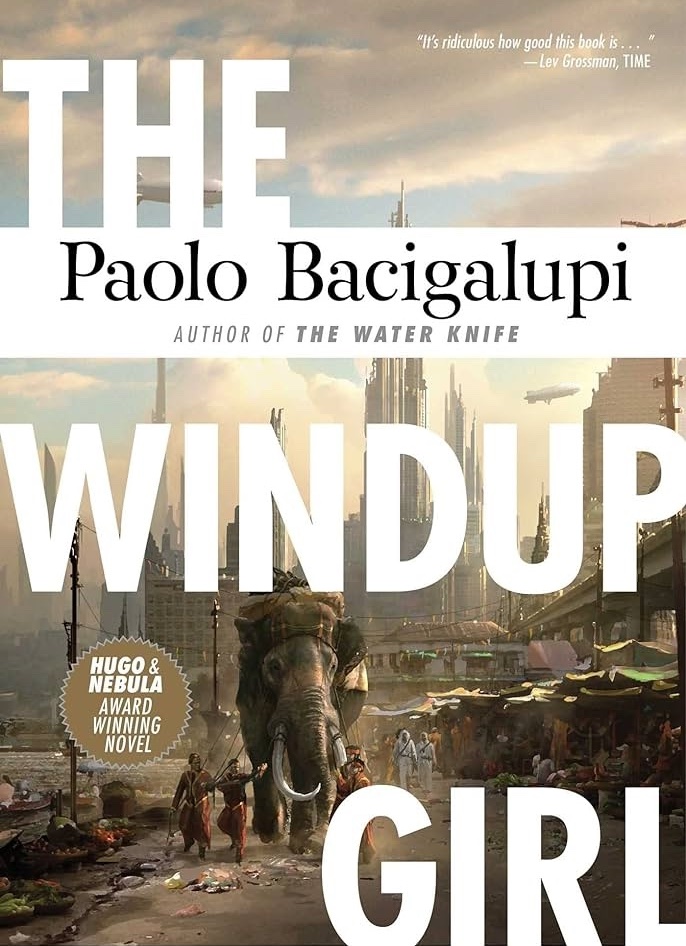

The publication of Paulo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl in 2009 marks an important stage in the writing of North American climate fiction. The novel was awarded the Nebula, Hugo, John W. Campbell, Compton Crook and Locus awards in 2010, as well as a host of other prizes. It is clearly inspired by previous sci-fi such as the early novels of William Gibson, or Ridley Scott’s pathbreaking film Bladerunner (1982), but it combines these and other sci-fi texts in in ways that make the role food and the food system play for socio-ecological breakdown unusually clear. Not all critics have praised the novel. It contains scenes of violent sexual abuse that are perhaps a bit too explicit not to connote misogyny. Thus, Simon C Estok (2021) has argued that the novel is informed by sexism and “racist Orientalism” and that it “reiterates rather than challenges many of the patriarchal values of the hero genre”. Even so, and as Estok also observes, The Windup Girl is essential reading if we want to understand how climate fiction from North America describes food, eating and the global food system.

The point of this (rather long) post is not to engage the considerable body of literary criticism that The Windup Girl has produced, but instead to briefly describe and engage the particular food future that the novel imagines. While most climate fiction utilizes food as a marker of future socio-ecological change, food, eating and the global food system are what drive the narrative of The Windup Girl. For the project that I am currently doing and that this blog is a part of, it is a quintessential text.

The story takes place in a future where what is referred to as a new “Expansion” or a “new global economy” is taking place. This is a development that follows in the wake of what the novel terms “the Contraction”. What contracted is, the reader understands, effectively what Immanuel Wallerstein has influentially termed the modern world-system. To summarize a very carefully researched and complex argument, Wallerstein argues that the world we currently live in has been structured by a capitalist economy that extracts resources and cheap labour from the peripheries of the system for the benefit of the core where resources have been refined and sold on a world market, and where the proceeds of this economy is accumulated. This is a system designed and operated by a host of actors, governments, multi-national corporations, banks, military organisations, and transportation companies and, for the past 400 years, it has created a radically uneven world where people in the peripheries have become relatively poor, while those in the core have become affluent. That said, the core has always been multiscalar and contained pockets of significant poverty. (More recently, environmental historian Jason W. Moore, noting that the world-system erodes not only human social worlds but also ecology, has proposed the concept of the capitalist world-ecology. More about this in another post).

The main driver of the early capitalist word-system/ecology was food and other consumables: sugar, rice, fruit, and tobacco. The market for such items in Europe created the triangular trade that moved food from North America to Europe, trade items from Europe to Western Africa, and slaves from Western Africa to North America. In the years that followed, the appearance of new resource frontiers in America and, increasingly during the nineteenth century, in other parts of the world, helped to extend this network across the entire world. This network consists of railways, interstate highways, airline corridors, shipping routes, pipelines and electrical or fibreglass cables. These enable the movement of foods, labour, energy and money across the planet so that tropical foods can be eaten at all times of the year also in Stockholm, Norwegian salmon can be part of sushi dinners in Tokyo, and oil can be piped from Alberta, Canada to Illinois in the US. It also makes it possible to transport food (such as cod caught in the North Atlantic) produced in one part of the world to other parts (China) where it can be more cheaply processed before being transported back to the local market). Alongside industrialized and invasive monocrop and cattle farming, this transportation network is a major contributor to greenhouse gasses and thus to global warming.

In The Windup Girl, the degradation of the soil, a host of soil-borne diseases, and the immanent need to curb the release of CO2 from fossil fuel transportation have caused the world-system to grind to a halt. This is effectively what the Contraction referred to in the novel means: a falling apart of the transportation networks that kept the old world-economy/system operational. At the start of the novel, there are signs it is recuperating, however. New modes of transportation (solar-driven “clipper” ships and lighter-than-air blimps) have made it possible to create new transportation routes. In addition to this, global food corporations have taken advantage of the prevalence of soil-borne diseases and pests such as “blister rust, Nippon genehack weevil and cibiscosis”. In a world where most natural food crops are struggling to survive, these companies are producing new, genetically modified strains that are resistant to the new blights and pests, but that are also sterile. This forces farmers to buy all their seeds from so-called “calorie companies” such as “AgriGen and PurCal” year after year. This new food order makes it virtually impossible for any part of the world to survive outside the budding “new global economy”. Without a steady flow of genetically modified seeds manufactured by these companies, people will starve. It is an enormously dark, yet not implausible, vision of the global, corporate food future.

Not all nations are hopelessly trapped in this new global economy, however. The Windup Girl takes place in Thailand, a nation that has managed to survive thanks to an extensive seedbank from which resistant and fertile strains can be derived. This makes the nation extremely interesting to the calorie companies; it is both a potential competitor that may decide to sell non-sterile seeds on the recovering world market and the owner of a genetic gold mine. The DNA strains contained within these seeds are of enormous value to the companies that must constantly produce new and resistant seeds, and that no longer have access to the genetic profiles of the various plants that we take for granted today. Thus, The Windup Girlrevolves around an attempt by a calorie company spy to gain access to the Thai seedbank and also to open Thailand to the new global economy; to extract its seed treasure and return the nation to its former semi-peripheral status.

In this way, the novel asks crucial questions not only about how the ongoing socio-ecological crisis was produced but also about how the existing system will adapt to crisis. In environmental humanities, significant attention has been devoted to understanding the role that capitalism and the world-system have played for global warming. As I discuss also in other posts, an increasing number of scholars have proposed that the driver of the unfolding crisis is not humanity as a species, but capitalism and the world-system (see Klein, Foster, Moore, Malm). Many of these scholars are located politically on the left, but climate researchers, intergovernmental organisations such as The Club of Rome and members of the IPCC or the UNFCCC are also making this observation. Even many scholars and initiatives fundamentally supportive of capitalism have observed that the pursuit of the profit that can be had from cheap food and labour is detrimental to the planet. Where they differ is in their analysis of how the ongoing socio-ecological crisis can be resolved: can capitalism turn green and thus resolve the ongoing crisis, or is capitalism a dead end for ecology?

Through its focus on the food system, The Windup Girl provides one logical answer to this question. In this future food fiction, the capitalist world/food system has found a way to thrive even from global ecological breakdown. For the calorie companies, soil-borne disease and resistant pests are a business opportunity; a way to cement the capitalist food system. The book even hints that some of the existing diseases were manufactured by these companies (that capitalist corporations would manufacture illnesses that they can then be paid to cure is explored in another seminal climate fiction: Oryx and Crake (2003) by Margaret Atwood). Thus, extractive capitalism is enormously adaptive and continues to thrive even in this post-breakdown world. As Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore propose in A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things(2018), capitalism can thrive even on the ruins of the ecological world. In Bacigalupi’s novel, it continues, as Moore argues, to reorganise not just social and economic lives, but ecology itself.

In this way, climate fiction explores future food world/systems in radical ways, forcing readers to consider their own location with this system, where the food they eat comes from, who benefits from the consumption of this food, and what food system futures lie ahead. It may also ask the reader to make choices not just about what food to invest in in the supermarket, and what food to put on the table, but about what drives the current food system in the first place. In The Windup Girl, one of the Thai protagonists decides to keep the seedbank from the invading calorie company forces. Rather than giving it up and making Thailand dependent on the new capitalist global food system, she collapses the levees that keep Bangkok dry in this inundated future, and relocates the seedbank to the hills. This is the ultimate choice posed by the novel: to surrender to the food system or to explore an alternative food order outside of the global system.