Alien: Romulus premiered worldwide on August 16 and has since done very well at the box office. This film is not exactly climate fiction, but it does take place on a (colony) world exhausted by extractive capitalism, and it features a host of young people who realize they have no future and that something has got to change. The young female protagonist Rain is essentially an indentured servant working for the infamous Wayland-Yutani corporation (the profit-hungry, multi-branch company that seeks to weaponize the alien species in all the films of the franchise). Rain has been working for the company on this colony for most of her adult life and when the film opens, she has finally filled her quota. She should be free to leave the planet for some other, less inhospitable planet. But when she visits the run-down company office to get her release papers, she is told the company has doubled her quota and that she will not get her papers until another 5-6 years have passed. Outside the company offices, in the dark and smog-filled morning, someone is endlessly screaming that the Wayland-Yutani corporation is evil and criminal.

This set-up clearly identifies extractive capitalism as the engine of what environmental historian Jason W. Moore calls socio-ecological breakdown (rather than simply climate change). By doing so, Alien Romulus speaks in unison with a number of other recent science/climate fiction narratives, from Soylent Green (1973) to the excellent Blade Runner 2049. There is much to like about its vision, but it soon becomes clear that its critique of extractive capitalism is performative at best. The film itself is a poorly constructed and fundamentally unoriginal mash-up of Alien, Aliens and Aliens Resurrection, with a bit of Lost in Space thrown in to distract you. It steals rather than borrows and the most noticeable theft is of late actor Ian Holm’s visage. Holm played an android in the first movie and in Alien Romulus, his face is digitally projected onto a torn apart but revivified android. As film critic Sam Adams observed, “Romulus is the first Alienmovie to feel like it might be a product of the WeylandYutani corporation itself, as mercilessly efficient as it is inhuman”. To add insult to injury, the acting is sub-par, and the plot twists are wildly improbable, illogical and annoying, to the extent that you wonder how this script ever got the green light. The only redeeming feature, at the end of the day, is the gorgeous images of space.

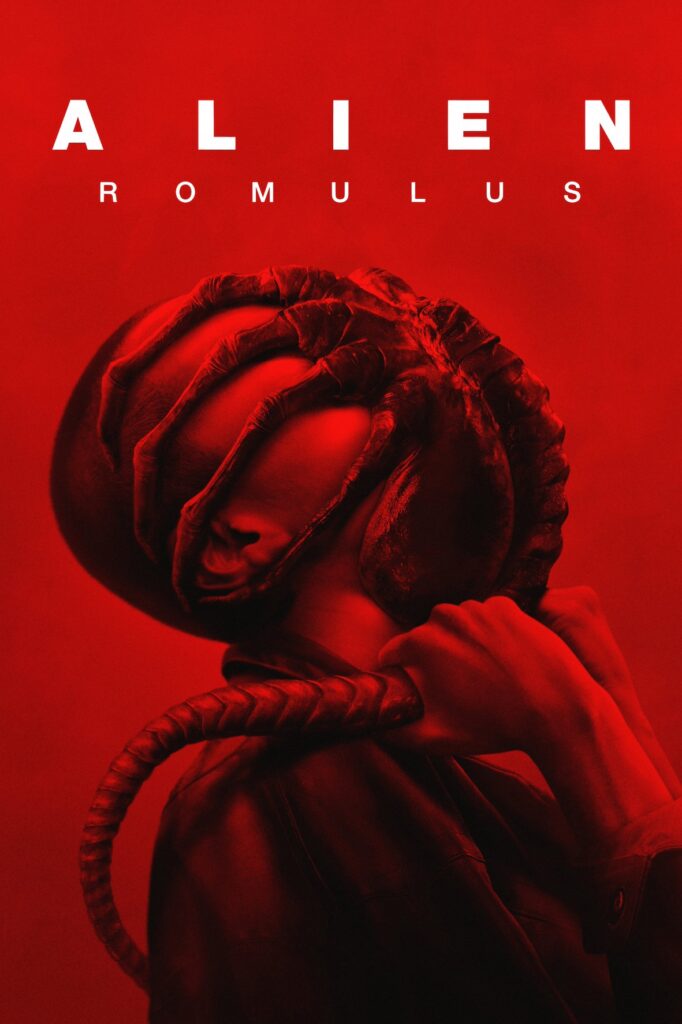

The film features some scenes of food and eating, and like much other science fiction horror, it casts human beings as themselves dispensable consumables. The poster image shows a parasitic “face hugger” attached to the head of one of the characters, and it looks almost as if they are eating each other. Also, it is not just the aliens who want to eat humans (if this is truly what they do – in this film it does not seem that they need any kind of sustenance to grow and evolve), it is also the inhuman corporation. This is an important story to explore, but even the first Alien, released in 1979, tells it much better than Alien Romulus. At this moment in time, there is a desperate need for good science fiction that helps us understand the systems, relationships and histories that have brought on planet-wide socio-ecological breakdown, and that imagines futures (and pasts) other than those programmed into the existing world-system. Science fiction is often apocalyptic and delights in images of total destruction. However, what is needed is, as Evan Calder Williams has argued, images that help us imagine “a destruction of totalizing structures”. There are big-business, mainstream films and television series that do gesture towards such destruction, including (curiously) the Star Wars spin-off Andor (2022). Alien Romulus does not.