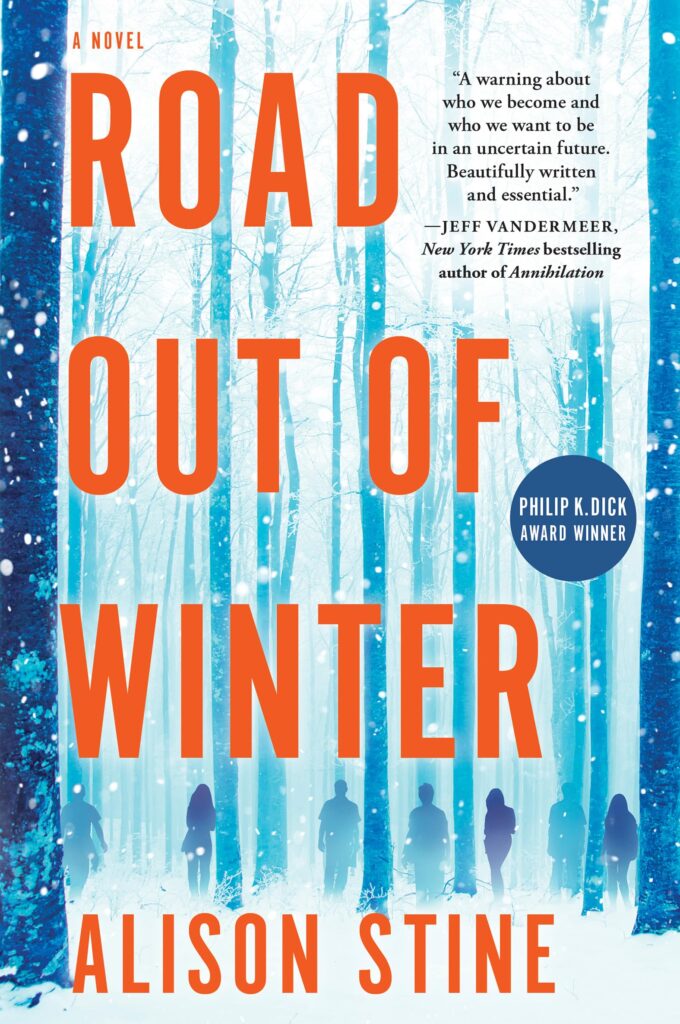

Alison Stine’s Road Out of Winter is a postapocalyptic climate narrative set in rural Appalachia that won the 2021 Philip K. Dick Award. The protagonist is 18-year-old Wylodine (Wil). She has recently been abandoned by her mother and the mother’s boyfriend Lobo, an abusive, small-time criminal. She is thus stuck in a trailer (euphemistically referred to as a “tiny house”) and expected to cultivate weed in the cellar of the main house, and what food crops the small farm might yield. Growing anything is getting increasingly difficult in this future where the weather has turned extremely cold rather than warm. At the beginning of the novel, the month of June brings sleet and icy winds rather than spring and Wil struggles to remain warm. When summer does not materialize, she understands, with the rest of her community, that she must abandon her home and travel south. The idea is to go to California where her mother is supposedly waiting for her. She joins up with another abandoned young adult, hitches the trailer to her battered pickup, and begins to journey south.

Road Out of Winter is an interesting climate fiction partly because it inverts the weather. This is not a future where the climate is too hot and dry, but instead too cold and wet, for growing food and thus for human habitation. It is also original by focusing poor, white people rather than the middle-class. Wylodine lives a life in the economic periphery of America, and she is used to having to ration food and other necessities. She is also surrounded by people who have long been preparing for some kind of cataclysm. Many belong to fundamentalist Christian orders, others to secular survivalist cults (the difference is not always apparent), and while she is located outside of these groups, she is part of the community they make up.

In this way, she is a very different person from many of the people that readers encounter in other climate fictions. Wil is not an upper-middle-class subject suddenly deprived of undeserved and erosive privileges – the most common figure in climate fiction from the Global North. Nor is she a competent, paramilitary, masculine survivor – another figure that populates many climate narratives from this part of the world. Even so, she is a very resourceful and decisive character. In particular, her ability to grow things makes her stand out. A childhood spent helping her mother’s boyfriend grow weed in the cellar of the house, under harsh, electric grow lights, has provided her with a crucial survival skill, one valued by all those who hope to survive the unfolding apocalyptic winter.

The fact that Wil is a “grower” is known in the area. Many have bought their weed from Lobo and are well aware that Wil knows how to make things sprout out of the cold earth. When Wil and her fellow traveller are herded into a camp of survivalist skateboarders, she first assumes that they intend to add her to their small harem of abused women, but it turns out she is wanted for her seemingly preternatural skill with plants. “Well, we’re gonna need a witch now. We’re gonna need to grow things to eat”, the leader of the skateboarders declares.

This is interesting because it recenters the productive (and reproductive) work of women at a time of socio-ecological breakdown. When such work is perceived as essential to survival, actors with power will attempt to harness it, turning women into commodities rather than agents in their own right. The naming of such women as “witches” recalls ancient patriarchal strategies employed to relocate women to the underground of the normative social order. Doing so legitimized acts of violence and thus increased control of women and the essential work they performed (and often still perform) in their communities. Thus, when the leader of the skateboard community resurrects the figure of the witch at a time of climate/food emergency, this serves a practical purpose. This sets Wil up as a figure that must be inserted into the local community as a liminal yet vital component. Her understanding of soil is vital to survival, and this is precisely what makes her dangerous to this community.

Wil refuses the role she has been forced into. She takes off with other survivors deeply uncomfortable with the disordered and violent community. As she continues her journey, she becomes increasingly disillusioned with the idea that she will be able to escape to a warm California and there reunite with her mother. She is no witch, but she does have the farming and personal skills that may make her the centre of a new community. In doing so, she connects to a prevalent, global trend. As studies show, women (and gender-diverse minorities) are more vulnerable to socio-ecological breakdown than men. But communities of women have also, as Dankelman and Naidu (2020) describe, begun to organize. If there is a road out of winter for Wil, such organizing will be vital.