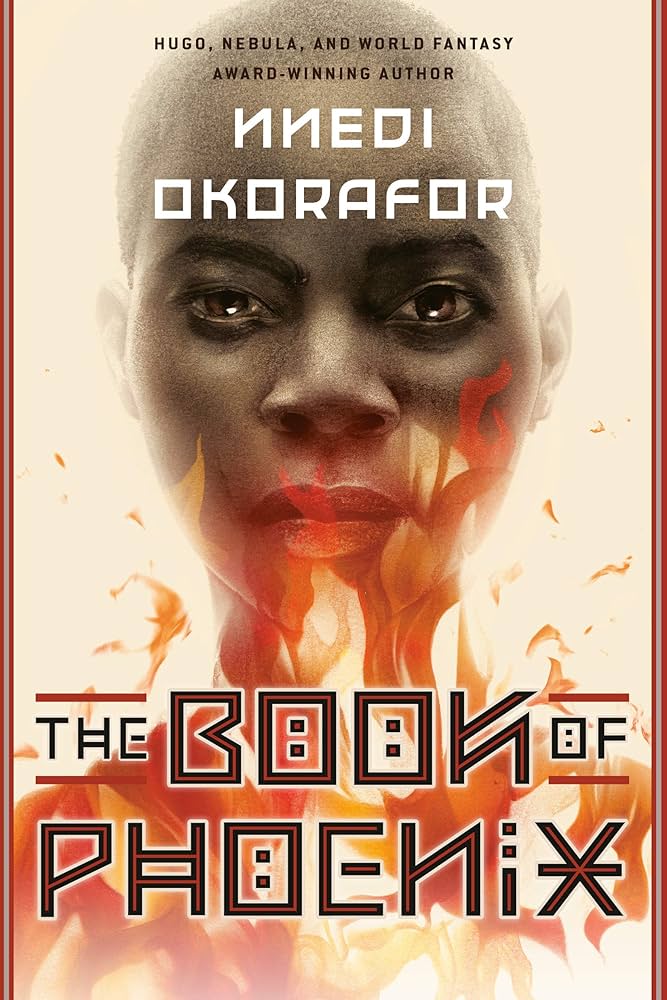

Like Tochi Onyebuchi, author of Riot Baby, Nnedi Okorafor was born in the US to Nigerian immigrants. Her writing thus explores socio-ecological breakdown both from the American and the African vantage. This double perspective is central to her novel The Book of Phoenix (2015) and aids in the book’s exploration of how the progress of global warming is connected to the long history of extraction out of which global warming has arisen. This critically renders the US as the primary agent of capitalist extraction on a planetary scale. The first-person narrator of the novel, the titular Phoenix, thus terms the nation “a strange and soulless land”. As in much other climate fiction, food plays an important role in the novel. However, unlike many North American climate fiction, the focus of this novel is not food scarcity. Instead, the novel uses food partly to designate cultural and social belonging and partly as an image of rebirth and restoration.

The Book of Phoenix is the prequel to Okorafor’s more widely read Who Fears Death (2010). Thus, the story has two timelines. The first, which frames the story told, is the distant future where the events of Who Fears Death is told. The other, which takes up most of the novel, is a less-distant future that explains how the dystopian future described in Who Fears Death came about. This future is in the form of an audio file or “memory extract” stored among debris from a long-lost world. It contains the first-person narrative of Phoenix: an “accelerated biological organism” or “SpeciMen” created by a company called LifeGen Technologies. As a biological experiment, Phoenix is property and thus deprived of human rights. With a great number of other SpeciMen – all people of colour –, she is contained in Tower 7, one of several experimental facilities spread across the world. Her best friend is a Saeed, another experiment who cannot eat regular food and who subsists on “glass, metal shavings, crumbles of rust, sand, dirt, those things that would be left behind if human beings finally blew themselves up” (13).

Phoenix and her fellow SpeciMen prisoners are deeply unhappy in their captive state, and before long, she succeeds not only in escaping the tower but in exploding herself in a gigantic ball of fire, destroying the tower and sections of the city around her (which turns out to be New York). Phoenix is aptly named, since, like the Phoenix of Greek mythology, she comes back to life after a few days. She exits the immediate area of destruction and stumbles into an Ethiopian restaurant. She is served “doro wat” with “drumstick and boiled eggs stewed in the spicy red sauce”, along with “a small mound of boiled cabbage and carrots” and “a mound of yellow curried lentils”. The plate is covered by “injera, a spongy delicious flat bread” (47). This is only one of many food descriptions in the novel that demand attention.

The point here is that despite being set in a time of increasing precarity and geopolitical tension, this is not a story about the lack of food. Instead, Okorafor connects the biospheric crisis to colonialism and extractive capitalism. After having eaten the splendid Ethiopian meal, Phoenix grows wings and flies across the Atlantic to Africa where she is pursued by the company that brought her into being. This provides ample opportunity to connect the erosion of social and ecological worlds to past and present colonialism. When Phoenix is captured, she is sent back to the US on an Exxon oil ship. As during the colonial era, the smell of “white colonial foreigners” is “Death” (97). In this way, The Book of Phoenixemploys (African) food to mark a sustainable type of human-earth relations. The problem, the novel suggests, is not a lack of food, but rather the colonial and capitalist principle that has transformed the world and its human population into extractable property. It is an important story to tell.