As described in this blog post, research into future ways of eating often considers three different diets: the Optimized Omnivore (essentially the EAT-Lancet diet) diet, the Novel and Future Food (new types of food including cell-cultured meat, insect protein, solar food) diet, and the Vegan diet. A lot of food science research is currently devoted to understanding the nutritional composition of these different diets and the costs of producing them, but it is also interested in how these new diets may be received by people. This, of course, is what climate fiction that features food and eating is also involved in. Like the food studies research described above, climate fiction thus explores futures where people eat insects and cell-cultured meat, and where they have turned to vegan or vegetarian diets. In addition to this, they also depict what can be termed Failed Future Diets where there is no functional food system at all, leaving people to scavenge for scraps in the ruins of modernity.

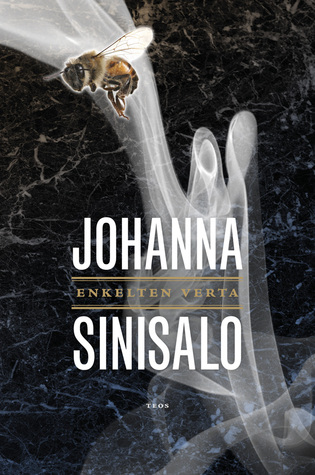

Most climate fiction from North America or the Nordic region depicts either a Failed Future Diet or futures where people have turned to Novel and Future Foods for sustenance. By contrast, there is only a small number of texts that record a turn towards the Optimized Omnivore or Vegan diets. One such novel is Johanna Sinisalo’s The Blood of Angels (2011/2014) a Finnish climate fiction first published in 2011 as Enkelten verta. Like much other climate fiction, it explores a future where the globe is warming, biodiversity is decreasing and tensions between people and states are increasing. In addition to this, it importantly investigates the attitudes, traditions and systems that resist profound transformations in the way people eat.

Much like Maja Lunde’s widely read and studied novel The History of Bees (2015), Sinisalo’s novel focuses on the collapse of bee populations across the planet. In the novel, the amateur beekeeper Orvo has just discovered that his bee queens have begun to die and that his colonies are collapsing. Colony collapse disorder is a well-documented problem, so the novel does address a known issue in this way, but the demise of Orvo’s bees also functions as a marker of biodiversity loss in general. It is easy to see how the death of bee populations is both a tragedy in its own right, and a catastrophe for plants and agriculture dependent on pollinating insects such as bees. In other words, growing food is very difficult without pollinators and, in The Blood of Angels, the death of bees in North America has caused food riots, rampant inflation and a large body of climate refugees where “those south of the US-Mexico border are finally glad to have the wall the Americans once built, with its barbed wire and guard towers” (17).

A few pages into the novel, Orvo’s worry over his bees is complemented, rather than overshadowed, by the sudden death of his son Eero. The circumstances of his death are not immediately made clear, but the reader is told that Eero, in his early 20s, was a vegan and an animal-rights activist who had begun associating with eco-terrorist groups. Before his untimely death, he participated in direct action against the industrial farming of animals and he also wrote two blogs. The first is the vegan blog called Eero the Animal’s Blog: Ponderings on our relationship with animals and the second is the activist Perfecting the Human Species: A blog about the animalist revolutionary army and its activities. In fact, a significant portion of the novel consists of blog posts written by Eero, and these sections also include comments from readers of the blog. These comments are sometimes conversational requests for a more detailed description of how the human-animal relationship should be understood, sometimes observations that the consumption of animal protein was central to the evolution of the homo sapiens, and sometimes evocations of food security. In addition to this, there are also clearly voiced threats: “Sooner or later Ordning Muss Sein, if you know what I mean. And it’ll be Endlösing for you hippies” (88), and claims that Eero’s attitudes and actions threaten to collapse “a law abiding business sector” (178).

Outside this retrospective communication between the dead Eero and the voices of various Finnish people, the mystery of Eero’s death is slowly unravelled. Towards the middle of the story (spoilers coming up) the reader is introduced to Eero’s grandfather (Orvo’s father), the returned American emigree Ari. Having been able to escape a United States in free fall, Ari is now making good money from industrialized animal farming in the area, and as such he has been targeted by Eero and the animalist revolutionary army he is involved in. To scare Eero and this army off, Ari has employed a couple of thugs who went overboard and took Eero’s life.

In this way, the book recalls the Greek tragedy famous for connecting the tribulations of the family to the life of the state, only in this case, it is not so much the state as the predominant, meat-oriented food system that forms the backdrop against which the deaths of both bees and sons play out. Indeed, while The Blood of Angels consistently asks difficult questions of those who embrace a vegan diet and commit low-grade terrorist violence in the interest of animal rights, it is ultimately supportive of a vegan future. It asks that human-animal relationships be fundamentally rethought and reenacted in ways that make the existing, meat-oriented and industrial food-system impossible. In doing so, it also envisions the types of resistance that such rethinking is likely to encounter.

As made clear, this resistance includes arguments connected to the role animal proteins have played in human evolution or to gendered food-culture preferences where meat=masculinity. However, the most important form of resistance in the novel emerges not from these historical and cultural resistances to a Vegan food future, but from the market and the existing global food system. After all, Eero is not killed because people dislike his espousal of Vegan principles, but because his grandfather is trying to protect his meat-based business model.

This is an important observation in the novel. Of the three future diets posed by future food science, Veganism is likely the least extractive, but also the least commodifiable. When trying to predict how a future turn to a Vegan diet (or to the EAT-Lancet diet) may be received, this is a major concern. While the production of plant/soy-based alternatives to meat has become a business opportunity, neither the EAT-Lancet nor the Vegan diet require such new foods. This fact is likely to feed organized resistance, leveraged both through affective statements that evoke tradition and culture, and via systematic border-making of the type that prevented the WHO-supported launch of the EAT-Lancet Commission in 2019.