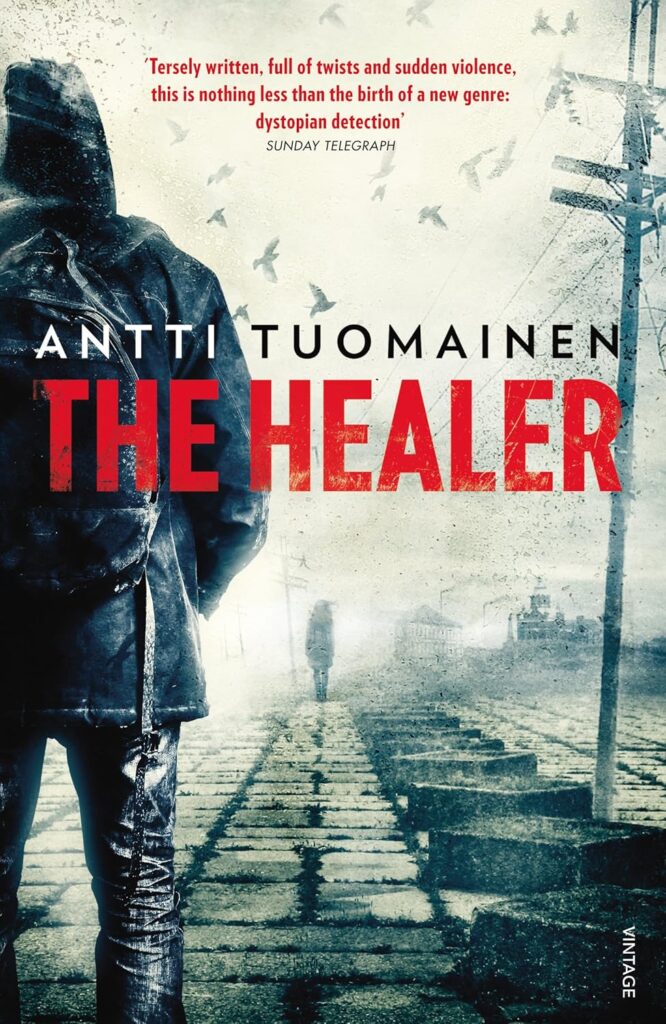

The Healer is a climate fiction crime thriller by Finnish author Antti Tuomainen. The novel was first published in 2010 as Parantaja and translated into English in 2014 (as well as into a number of other languages). As a relatively early Nordic cli-fi novel, it has amassed a certain critical heritage. It is often seen as a trailblazer of both Nordic climate fiction and a new type of Scandinavian Noir. Crime fiction scholar Stewart King calls it an example of “Crimate Fiction”. However, a persistent motif in the novel that critics have mostly ignored is food. This post is a first engagement with this aspect of the novel.

The Healer takes place in a future where global society is rapidly collapsing:

The southern regions of Spain and Italy had officially been left to their own devices. Bangladesh, sinking into the sea, had erupted in a plague that threatened to spread to the rest of Asia. The dispute between India and China over Himalayan water supplies was driving the two countries to war. Mexican drug cartels had responded to the closing of the US-Mexico border with missile strikes on Los Angeles and San Diego. The forest fires in the Amazon had not been extinguished even by blasting new river channels to surround the blaze (4).

In the novel, this development has generated some 650-800 million refugees, some of which have escaped into the Nordic region. Helsinki, where the story takes place, is home to many of these climate refugees. However, Finland is also crumbling under the pressures caused by a dismantled world ecology. The people who can afford it are either moving even further north into newly erected gated communities, or hiring private security firms to keep their homes safe as society falls apart. It is a vision of the future that has been rehearsed often in climate fiction.

The general idea behind this type of depiction is, of course, that by painting a picture of the future as enormously dark and hopeless, readers will want to mobilize against rampant climate change. This model does not necessarily hold, however. There is research that suggests that apocalyptic climate fiction stories risk paralyzing readers, rather than encouraging them to action. In stories such as Cormac McCarthy’s prize-winning and utterly dark The Road (2006), a father and a son wander aimlessly and hopelessly through an utterly ruined landscape where there is no food except the odd can left behind by long-gone people or, horrifically, other starved wanders. Such a story may be deeply disturbing and worrying, but it may not produce a reader interested in advocating for a different relationship to the planet or to their society. Indeed, McCarthy’s novel never bothers explaining why ecology has collapsed.

By contrast, The Healer is very interested in helping the reader understand why the world is collapsing, and food plays an important part in this explanation. The first-person protagonist of The Healer is named Tapani Lehtinen and in the opening of the book he has just lost touch with his journalist wife Johanna. She has been investigating a string of violent crimes where entire families have been brutally murdered by a serial killer calling himself “the Healer”. To the Healer, these killings are not crimes but just retribution: the people he murders are leaders of the extractive industries that have been central to the warming and pollution of the planet. When Johanna disappeared, she was working on a story where the wife and three small children were murdered in front of a father who is “the CEO of a large food company and an advocate for the meat-processing industry” (24). This is how food enters the conversation in the Healer: as a profoundly erosive system.

Food also appears in many other ways in the novel; as a marker of privilege (the culinary school in Helsinki has shut down, the reader is told), system breakdown (coffee is becoming increasingly scarce in a city that is virtually fueled by it) or cultural and social belonging. Also, the novel does not make a hero out of the radical and militant Healer. In fact, Tapani discovers that an accomplice of the Healer has managed to commodify the acute insecurities the Healer’s killing spree has created. Whenever a murder is committed, the demand for private security booms in that particular area. The accomplice has catered to this demand, making a fortune large enough to allow himself and the healer to join the exodus of the rich escaping Helsinki.In this way, the novel is ultimately a scathing indictment of extractive capitalism in its various forms, and the food industry is clearly perceived as an important element of this overall system. In other words, the novel recognizes the role that the existing food system and the meat-heavy diet it promotes play for planetary-scale ecological breakdown. There is a discernible relationship between the forest fires, the relentless rain and the intense conflict that serves as the novel’s background, and the prevalent food system. The novel thus suggests that to avoid the darkness it evokes – a future in which the “fight” over the future has been won by “a few thousand people who were already super-rich, who once again masked their own interests under the mantle of economic growth for the common good” (138-9) – this relationship must be addressed in the present. In the specific future the novel narrates, time has run out for such action and nothing remains except futile escape and pointless, performative cruelty.