This is another too-long blog post. Sometimes, you just have to give a novel the space it demands. So here goes:

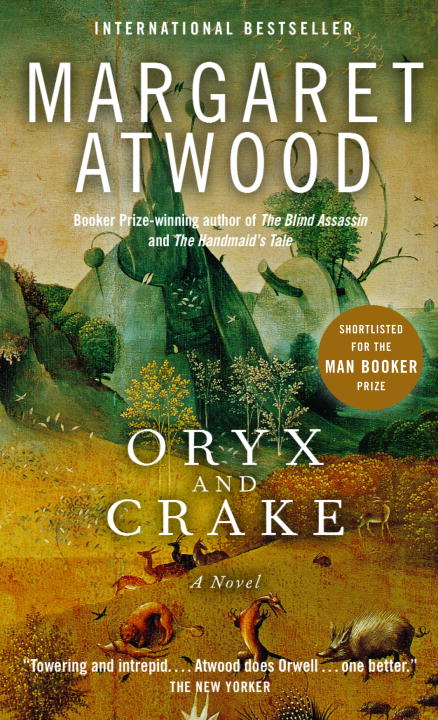

One of the most critically acclaimed and influential climate fictions from North America is Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake. Published in 2003, it was written at a time when the concept “Anthropocene” had only begun circulating in climate research, long before initiatives such as the EAT-Lancet Commission had brought wide public attention to the role that the food system plays for global warming. It also predates much research that has demonstrated how profoundly connected the existing global food system is to the dominant capitalist world system; how these seemingly discrete systems are essentially one and the same. Even so, her novel presciently makes many of the points that are central to more recent climate science and scholarship. Even so, some historical details and the strange and apocalyptic unfolding of the plot appear to resist what is arguably the text’s main argument: that extractive and ruthless capitalist cultures are wrecking lives, ecologies, species and sustainable foodways.

Oryx and Crake takes place in a world notably similar to that imagined by Octavia Butler in her similarly prescient climate fiction The Parable of the Sower (1993). As in Butler’s novel, privileged people gather in gated communities (called “compounds” in Atwood’s novel), while the less fortunate eke out increasingly unprotected and miserable lives in the “pleeblands”. The difference is that while the (black) protagonist of The Parable of the Sower is forced to leave her poorly fenced-in and eventually obliterated community, the main characters of Oryx and Crake belong to the privileged strata and live lives of comparative safety and luxury in the compounds. These are effectively corporate cities where microbiologists and geneticists invent new pharmaceuticals and food for a global and fiercely competitive market. The walls and security forces (CorpsSeCorps) of the compounds exist to protect the inhabitants from the random violence of the pleebland and the carefully orchestrated attacks performed by bioterrorists who work to sabotage the (profoundly unethical) research done within these cities. However, the most serious threats emanate from other compounds, where researchers are working on similar projects and want the competition out of the picture. Pressured by the slowly unravelling capitalist crisis, corporations recognize no laws except the need to increase profit. To make sure that there is a constant demand for expensive vaccines, pharmaceutical companies produce the viral and bacterial illnesses these vaccines are supposed to cure.

This is a future where many of the predictions issued by climate scientists have come about. In the novel, the reader is told how “the coastal aquifers turned salty and the northern permafrost melted and the vast tundra bubbled with methane, and the drought in the midcontinental plains regions went on and on, and the Asian steppes turned to sand dunes, and meat became harder to come by,” so that socio-ecological breakdown is brought to all parts of the planet (although people in the compounds are still living comfortable lives). As this passage suggests, this development creates a shortage of (meat-based) food. Thus, genetic experiments on pigs designed to produce humans with new and vital organs evolve into projects designed to also feed humans meat. Chickens are genetically modified until they consist only of meat, bone and a small mouth serviced by an even smaller brain capable of keeping the chicken eating but nothing else. Those who cannot afford “real”, meat-based food or whiskey made from actual malt have to digest cans of “Sveltana No-Meat Cocktail Sausages” or similar meat-replacement products.

Oryx and Crake makes it adamantly clear that what is eroding social and ecological worlds in this climate future is capitalism and corporate greed. Thus, it also connects the industrialized food system to the warming and erosion of the planet. At the same time, it shows how the same industrialized food system adapts to biospheric breakdown. The erosion of the biosphere and the difficulty to grow food become, for the companies that run the compounds, business opportunities. In fact, when disasters slow down, these companies find ways of accelerating them. In this future, pharmaceutical companies manufacture viral plagues in order to find an eager market for their vaccines. While illnesses and food shortages may be catastrophic for vulnerable communities, they present predatory capitalism with new frontiers to explore.

The main characters of the novel – the absurdly brilliant geneticist and microbiologist Glen “Crake” and the far less clever, but still reasonably privileged Jimmy “Snowman” – understand how the system works. The miserable Jimmy has resigned himself to the state of the world and is stuck writing advertisements for the many pointless and often dangerous products his compound is peddling. Crake, however, has devised a plan that will put an end to it forever. Rather than allowing the system to keep destroying the planet and its many species, he has engineered both a plague that will eradicate all human life, and a new type of (plague resistant) human being fundamentally different in desires and relationality from the homo sapiens. This new type of human has been genetically engineered so that it will live with, rather than on top of, nature. The project is a success. Almost all humans die, and the new species, referred to as Craker’s live on into a very uncertain future.

The point here is that Crake’s radical, genocidal antidote to biospheric breakdown is fundamentally Anthropocentric. Crake’s assumption is that the havoc he inhabits is anthropogenic rather than systemogenic. He (and Atwood) may recognize that the world he inhabits has been made by, and is maintained by extractive capitalism, but in Crake’s analysis, predatory capitalism is a fundamentally human construct. It seems to him that the homo sapiens have been genetically programmed to be capitalist, greedy and to destroy the planet. Because of this, and in order to halt the progress of extinction, the existing type must be obliterated and a new form of humanity must rise, one genetically different from the old version.

The idea that humanity is the agent of biospheric breakdown is central to the Anthropocene concept, of course. Also, climate scientists such as Paul Crutzen and Will Steffen have argued in the article “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?” (2019) that humanity began progressing towards global warming on the day that homo erectus discovered how to control fire. Similarly, environmental historians such as Dipesh Chakrabarty have also centred the human species as the agent of environmental breakdown. When this happens, it is logical to ask the question: how do we prevent humans from being human in this destructive way? If the homo sapiens were always programmed to produce a mass extinction, how do we prevent this from unfolding? This is the precise problem Crake has so drastically resolved in Atwood’s novel.

It is not strange that Crake, located within the embrace of a hyper-capitalist compound, should come to this conclusion. The world outside the gates of this community is accessible to him primarily through (paid-for) media. He thus discerns what is often termed the Global South through television news that mostly reports on the catastrophes and carnage that occur in this region, pornography, and snuff film. From his vantage, humanity is a virus that is destroying the planet; a creature incapable of restorative practices.

But, as I keep returning to in these posts, there are other ways of thinking about the forces that are warming the planet. As the Club of Rome Earth for All initiative argues, what drives biospheric breakdown is not the human species but instead what the authors call “rentier capitalism”. A similar analysis emerges out of the eco-socialist work of John Bellamy Foster, Jason W. Moore, Naomi Klein, Andreas Malm, and Hannah Holleman. As Moore has argued, a better word for the current period of biospheric breakdown is Capitalocene. Unlike “Anthropocene”, this mentions the system that is currently fuelling both the global food system and global warming. This concept also helps us understand that the practical solution to stopping socio-ecological breakdown is not the total obliteration of the human race. In the words of the Earth for All initiative: “Re-programming our economies so that they work for both people and the planet is the solution to today’s major challenges”.

There are a few climate fiction stories that try to imagine what such economic transformation might look like, (and what such transformation might mean for how we produce, transport and consume food). Kim Stanley Robinson’s enormously ambitious The Ministry for the Future is one and this project attempts to identify others. But many novelists never undertake this particular imaginative leap and instead get stuck in apocalypse, extinction, emergency and genocide. It perhaps makes for exciting stories, but not ones that help people on this planet to build new and sustainable, secure and economically just (food) worlds.